This Lancet article gives an optimistic but plausible take on what would happen to health spending if we expanded the current version of Medicare to cover all Americans: a 13% drop in health spending.

Why Optimistic

The big problem I see in the article is that it claims to be evaluating what would happen if we passed the Sanders Medicare for All proposal, which involves changing current Medicare in a way that would make it much more expensive- removing coinsurance and deductibles. Removing cost-sharing would increase utilization for most everyone, not just people who are currently uninsured or “underinsured” (which they count at a combined 79 million); studies on Medigap insurance suggest this could raise spending 33% relative to standard Medicare. The Lancet study ignores this, but it would turn their predicted 13% spending reduction into a nearly 20% spending increase.

Why Depressing

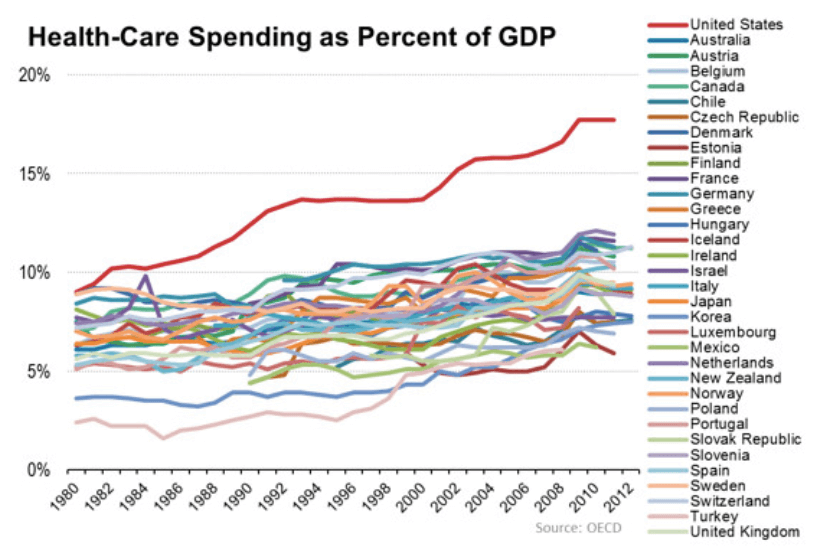

Still, I like having a study like this around, as it gives a clear presentation of what one version of Medicare for All might look like and where various savings and costs might come from. The depressing part is that even if all of their optimistic projections are true, and if a giant reform like Medicare for All actually happened, America would still have by far the highest health care spending in the world, with at-best average results. The latest OECD data shows the US spending 16.9% of GDP on healthcare, with Switzerland in a distant second place spending 12.2%. If Medicare for All, the biggest reform of the US health care system since at least 1965 and possibly ever, actually worked as predicted here, we would be spending 14.7% of GDP on health care- still far more than Switzerland or anywhere else (which makes sense as Medicare is costly by international standards). The article doesn’t put their mortality estimates into life expectancy terms, but the 68000 fewer annual deaths they predict represents a 2.4% drop; a 2.4% increase in life expectancy would bring us from 78.6 years to 80.5 years, still on the low end for rich countries.

This shows how our problems are bigger than just insurance and health financing, but even ‘just’ fixing the financing part (either with M4A or any other major reform) is unlikely.

Why It Won’t Happen

The authors argue that Medicare for all is politically feasible because, under their somewhat optimistic assumptions, the average American saves some money, while the average doctor and hospital roughly breaks even (Medicare generally pays less than private insurance but more than Medicaid and charity care), with the savings coming from lower administrative costs, lower fraud, and lower pharmaceutical prices. But I think this misreads the politics; while the Median Voter Theorem can be a good first approximation, the US political system tends to favor the well-off, special interests, and those who trying to maintain the status quo rather than change it. The paper itself makes clear who some of the losers from Medicare for All would be: private insurers, pharmaceutical companies, doctors and hospitals with a higher-than-average share of privately insured patients, and most people who spend a less-than-average share of their income on health care (which higher-income people tend to do; they also vote at higher rates). Further, “936,000 administrative positions and 746,600 positions in the health-care insurance industry are estimated to become redundant”. Many influential groups would suffer concentrated costs that would motivate dedicated lobbying effort against, while the largest benefits would be concentrated among the ~10% of Americans who are uninsured, who tend to be relatively poor. The ACA was a much smaller reform that did much more to buy off or otherwise placate most of these interest groups, and it still barely passed and lead to a huge political backlash, a lesson that at least some major relevant political figures took to heart.